Alzheimer’s Today recently published an article authored by Connected Horse’s Isabel Soloaga, Living in the Present Tense.

When my Granddad Mitchell died of dementia at 86, he still lived alone on the East Bay ranch he’d won in a bet after returning home from serving in WWII. He always refused to leave. That was home: sitting on the front porch, watching his horses and the hummingbirds. His life and death remind me to take my life into my own hands.

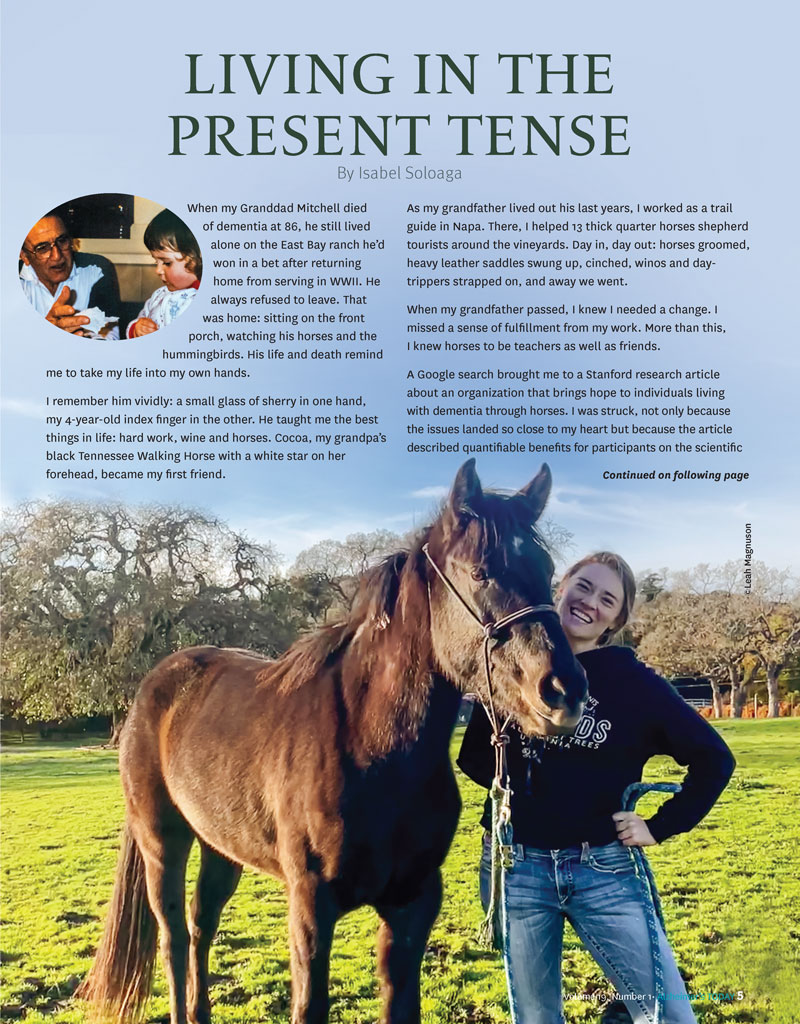

I remember him vividly: a small glass of sherry in one hand, my 4-year-old index finger in the other. He taught me the best things in life: hard work, wine and horses. Cocoa, my grandpa’s black Tennessee Walking Horse with a white star on her forehead, became my first friend.

As my grandfather lived out his last years, I worked as a trail guide in Napa. There, I helped 13 thick quarter horses shepherd tourists around the vineyards. Day in, day out: horses groomed, heavy leather saddles swung up, cinched, winos and day- trippers strapped on, and away we went.

When my grandfather passed, I knew I needed a change. I missed a sense of fulfillment from my work. More than this, I knew horses to be teachers as well as friends.

A Google search brought me to a Stanford research article about an organization that brings hope to individuals living with dementia through horses. I was struck, not only because the issues landed so close to my heart but because the article described quantifiable benefits for participants on the scientific level. These included significantly lowered depression and anxiety in both people living with dementia and their care partners. I wanted to learn more.

I signed up to volunteer with the organization, Connected Horse. In the presence of the horses, I watched individuals who couldn’t speak when they arrived suddenly open up about their childhood experiences with horses. Shaky men and women living with dementia were leaving their walkers behind to groom, halter and lead horses. Somehow, the horses knew exactly what to do. They matched their hooved steps with their new leaders’ and moved gently with the participants. The more I saw, the more I was convinced the program was not only a critical intervention in the struggle with dementia but transformative at every level.

The program, the first of its kind, fills a gap in existing healthcare options for people living with dementia and the people who care for them. Where personal relationships and medical needs collide, there remains a sincere need for professional support. This is where the lessons from horses prove so powerful.

Horses live in the present tense, highly attuned to their surroundings. Without language, horses communicate complex emotions, form tight herd bonds and remain connected to their family throughout their lives. They are living proof that experiencing joy together can happen throughout our lives, and that even after language skills might be lost to a disease, it is still possible to connect meaningfully to those around us.

“With Connected Horse, I could finally breathe, slow down and just be,” says my friend Tammy, who lives with early-onset dementia. “The horses knew that I needed them.”

Like my grandfather, Tammy is living life on her own terms.

An avid traveler, she is planning to visit Italy as soon as she completes her participation in a six-month research study on the impact of a vegan diet and exercise on early-onset dementia.

“I refuse to let dementia define me,” Tammy says. “I’m still just me.”